Dysautonomia Explained

October is International Dysautonomia awareness month. This surprisingly common ‘invisible’ condition is one that many of us likely haven't heard of. In this article we will aim to understand more about what dysautonomia is, what conditions it comprises, potential causes and what can be done to treat it.

What is it?

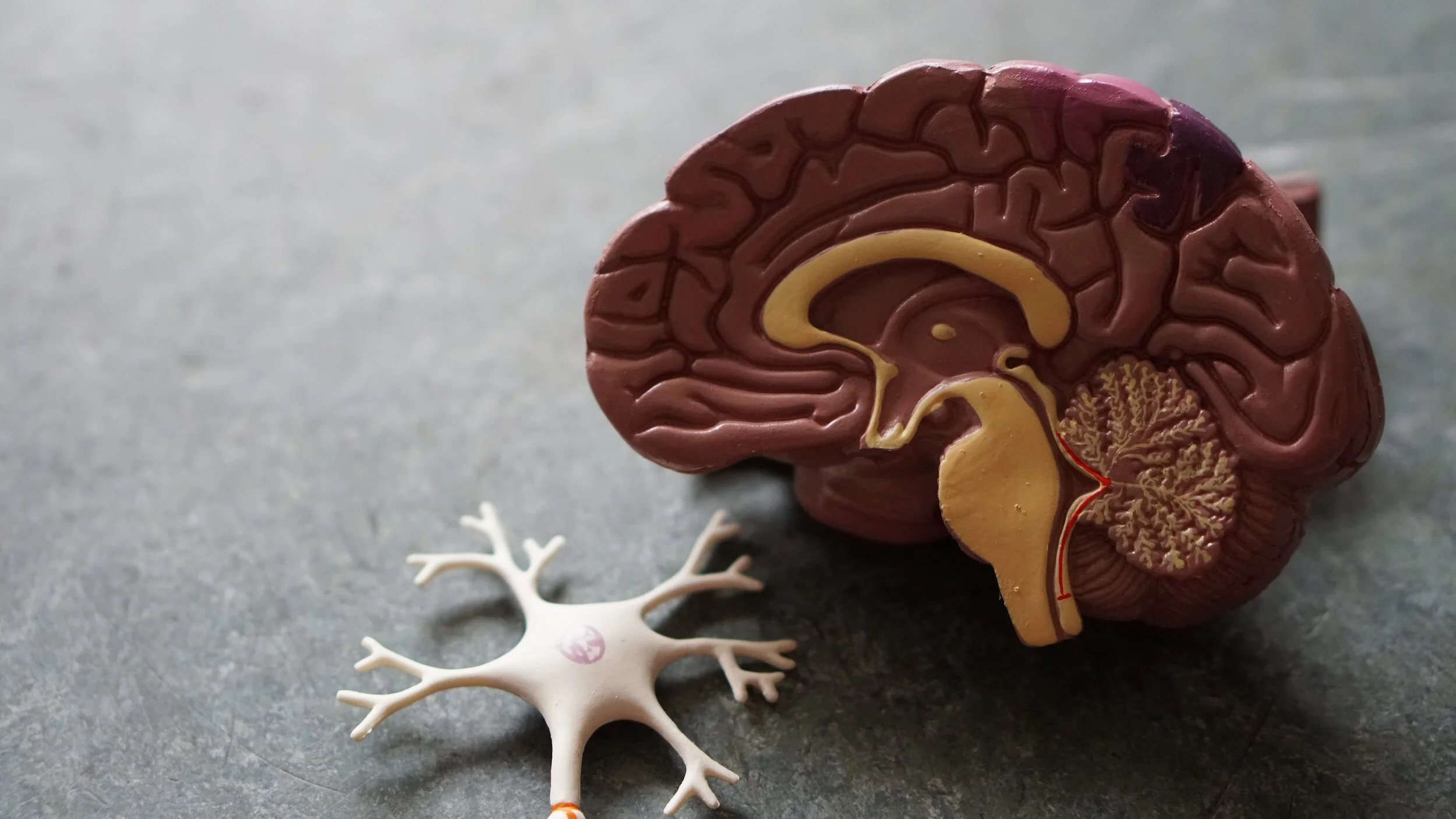

Dysautonomia is an umbrella term that describes several different medical conditions that arise from “dysfunction” in the Autonomic Nervous System. The Autonomic Nervous System controls the "automatic" functions of the body that we do not consciously think about, like heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, dilation and constriction of the pupils of the eye, kidney function, and temperature control. An important thing to understand about the autonomic nervous system is its two component subsystems - the Sympathetic (Fight/Flight/Freeze) Nervous System and the Parasympathetic (Rest/Digest) Nervous System. People living with various forms of dysautonomia have difficulty regulating these systems, which can result in any of the following symptoms:

Chronic lightheadedness/dizziness

Fainting/Syncope

Fatigue

Unstable blood pressure

Shortness of breath not explained by another cause

Excessive sweating, flushing

Dry eyes and mouth

Abnormal heart rate

Irritable bowel symptoms

Bladder dysfunction

Sensory changes - burning, tingling, numbness not explained by another cause

Dysautonomia can occur as its own disorder, without the presence of other diseases. This is called primary dysautonomia. It can also occur as a condition of another disease. This is called secondary dysautonomia. Although this terminology is by no means authoritative or exclusive. Research on dysautonomia is still emerging, and it should be stated that there isn’t agreement on what dysautonomia even strictly means scientifically.

But medical science is a strict discipline, often limited by its reductionist tendencies. It tends to require specific biological evidence to prove the existence of disorders like dysautonomia. Failing to realise that many of the body’s systems work together in an emergent fashion, leading to symptoms/diseases that can't be understood in isolation, rather they require a broader systems level view to make sense of what is happening.

Some conditions/syndromes that Dysautonomia is thought to cover/be involved in:

Orthostatic intolerance/hypotension (e.g. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome/POTS) - difficulty with changing/regulating blood pressure when standing, moving or changing positions (e.g. standing up)

Vasovagal Syncope - otherwise known as neurally mediated syncope (NMS), is a form of syncope where the autonomic nervous system suddenly fails to maintain an adequate vascular tone resulting in hypotension (low blood pressure) and bradycardia (low heart rate) causing temporary loss of consciousness

Hypermobility Disorders - a broad family of conditions where people have very flexible joints. It can lead to ongoing pain, movement and postural control challenges

Functional gastrointestinal disorders - a group of disorders characterised by chronic gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (eg abdominal pain, dysphagia, dyspepsia, diarrhoea, constipation and bloating) in the absence of demonstrable pathology on conventional testing.

Alterations in body temperature and sweating - due to changes in the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems) functioning, it is common to experience abnormal changes in body temperature and sweating.

Inappropriate sinus tachycardia - syndrome characterised by a sinus heart rate inexplicably higher than 100bpm at rest that is associated with symptoms like palpitations, dyspnea or dizziness

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome - group of inherited connective tissue disorders caused by abnormalities in the structure, production, and/or processing of collagen. The symptoms of EDS vary by type and range from mildly loose joints to serious complications.

Autoimmune autonomic ganglionopathy - a condition in which the body's immune system mistakenly attacks and damages certain parts of the autonomic nervous system

Pure autonomic failure - a neurodegenerative condition of unknown cause that leads to orthostatic hypotension and other symptoms related to autonomic nervous system failure/dysfunction

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome - a condition in which one experiences repeated episodes of the symptoms of anaphylaxis – allergic symptoms such as hives, swelling, low blood pressure, difficulty breathing and severe diarrhoea

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) - dysautonomia seems to occur in CFS primarily as disordered regulation of cardiovascular responses to stress (e.g. elevated HR/BP)

Multiple system atrophy - a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterised by a combination of symptoms that affect both the autonomic nervous system (the part of the nervous system that controls involuntary action such as blood pressure or digestion) and movement. The symptoms reflect the progressive loss of function and death of different types of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome - a painful and disabling condition that usually manifests in response to trauma or surgery and is associated with significant pain and disability. CRPS can be classified into two types: type I (CRPS I) in which a specific nerve lesion has not been identified and type II (CRPS II) where there is an identifiable nerve lesion.

Sjogren’s Syndrome - a rare systemic autoimmune disorder characterised by dry eyes and dry mouth.

Long COVID - dysautonomia is believed to occur secondary to long COVID, where patients experiences long term disability post COVID infection. Symptoms reported in Long COVID primarily include debilitating fatigue, breathlessness, headaches, muscle and/or joint pain, brain fog, memory loss, sensation of pressure on the chest, palpitations, nausea, and dramatic mood swings in combination with exercise intolerance.

Parkinson's Disease - Because Parkinsons involves lesions to the parts of the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic), the disease seems to be not only a movement disorder with dopamine loss in the nigrostriatal system of the brain, but also a dysautonomia, with norepinephrine loss in the sympathetic nervous system of the heart.

What causes it?

Due to its varied and heterogenous presentation, Dysautonomia can’t reliably be explained by singular causes as often can be done in other disorders/conditions. It is important to consider each individual and the other conditions they may be diagnosed with to paint the clearest picture possible. However we still are in the early stages of research into the many presentations of dysautonomia, and the pathophysiology underlying the different syndromes it encompasses. Thus there is still a lot of uncertainty as to why people experience the symptoms they do. Current pathophysiological drivers that may be implicated include:

COVID-19 - it remains unclear whether dysautonomia associated with long COVID-19 results directly from autonomic-virus pathway or post-infectious immune-mediated processes. But it's clear that as many as 1 in 10 people who contract COVID-19 subsequently develop long COVID symptomatology that is partially explained by dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system.

Other Viral Infections (Epstein-Barr, Hepatitus C or HIV) have also lead to subsequent development of dysautonomia and chronic fatigue symptoms through mechanisms we don’t yet fully understand.

Small fibre neuropathy - is a subtype of nerve tissue damage characterised by selective involvement of unmyelinated or thinly myelinated sensory fibres. Its pathogenesis includes a wide range of immune-mediated, metabolic, toxic, hereditary and genetic disorders. Small fiber neuropathy has been implicated in a range of conditions associated with dysautonomia, such as Sjogrens Syndrome, POTS, and CFS.

Autoimmune disease - the nervous and immune systems function so closely together they could almost be considered the same system. Evidence of autoimmune pathophysiology has been detected in patients with dysautonomia, particularly POTS, CFS and CRPS.

What can be done to treat it?

There is usually no cure for dysautonomia. But its secondary forms may improve with treatment of the underlying disease. In many cases treatment of primary dysautonomia is symptomatic and supportive. Common treatments include:

Education - knowing more about dysautonomia, what it encompasses and what can be done reduces the very common experience of uncertainty and stress in those experiencing the condition. Knowing more also helps patients ask better questions of their health professionals, ensuring they receive the care they need.

Pages like https://www.dysautonomiasupport.org/, http://www.dysautonomiainternational.org/, and https://thedysautonomiaproject.org are great organisations to get patient resources from.

Hydration/Salt consumption - to combat hyper/hypotensive changes, alterations to fluid and salt consumption are recommended. For example in orthostatic hypotension, higher salt and water consumption can assist in maintaining higher blood pressure in when standing or changing postures

Medications - this will always be individualised, and best discussed with a medical professional trained and familiar with the management of dysautonomia. For information on specific medications see - https://www.dysautonomiasupport.org/medication-management/

Nutritional considerations - similar to above, nutritional considerations are always individualised and best discussed with an accredited practising dietitian. However common recommendations include smaller and more frequent meals to mitigate post meal blood pressure drops, and keeping a food diary to monitor the effects of certain foods and beverages on your symptoms

Psychological considerations - people with dysautonomias tend to experience impairments in attention, memory, and executive function, along with moderate depressive and anxiety symptoms. There is thus an essential role of Psychological counselling/therapy in easing the burden of these symptoms/impairments and providing strategies and skills to better manage them.

Sleep - sleep disturbances are common in those with some variants of dysautonomia due to changes in autonomic arousal. Thus it is strongly recommended to develop good ‘sleep hygiene’ by adhering to a regular sleep routine, reducing exposure to stimulating lights, foods and beverages prior to bedtime, along with limiting daytime sleeping.

Exercise - can be very beneficial for those with dysautonomia. It is recommended that patients participate in aerobic and strength training. However it needs to be adjusted to each patient’s individual needs/symptoms. Sometimes exercise needs to be commenced in a semi or fully recline position due to orthostatic intolerance, but can be progressed towards an upright position over time. Consult with a Physiotherapist or Exercise Physiologist knowledgeable in dysautonomia management before commencing an exercise program. Yoga in particular can be a helpful physical activity to both improve physical functioning, but also autonomic nervous system regulation through the breathing practices included.

Compression garments - Compression garments have been shown to improve symptoms of orthostatic intolerance. One particular study showed that abdominal and lower body compression reduced heart rate and improved symptoms during a tilt test in adult patients with POTS.

Counterpressure manoeuvres - positions that maintain or increase blood pressure on those with syncope or orthostatic intolerance. Common examples of counterpressure manoeuvres include buttock clenching, squatting, and whole body tensing.

Thermoregulation - dysautonomia can lead to issues with body temperature regulation where patients experience intolerance of either high or low temperatures. Helpful strategies to manage heat intolerance include wearing cooling vests, ice packs or the use of air conditioning. Helpful strategies to increase low body temps include layered clothing, air conditioning and heated or weighted blankets.

Energy conservation strategies - as people with dysautonomia often experience debilitating fatigue and fluctuating energy levels, it can be helpful to use energy conservation strategies like activity diaries, priority lists and scheduled periods of rest. These approaches always need to be individualised with your GP, Physiotherapist or Occupational therapist.

Dysautonomias are a complex array of disorders. And often difficult and delayed to diagnose. To best manage them it’s important to get the most accurate diagnosis possible. But even in absence of a diagnosis you can improve your symptoms and quality of life by working with a team of health professionals including a General Medical Practitioner, Physiotherapist, Dietitian and Psychologist.

When it comes to Physiotherapy for Dysautonomia, it's important to take a broader approach to improving function. Treatment will primarily focus on building tools and skills to improve autonomic nervous system regulation (e.g. breathing exercises and mindfulness practices) along with personalised exercise programs to not only improve autonomic regulation but strength, aerobic capacity and ultimately participation in your valued life activities.

If you have any questions about managing your Dysautonomia, or are interested in booking a consultation send me an email.

References

Dysautonomia | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2022). Retrieved 10 October 2022, from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/dysautonomia?search-term=dysautonomia

Identifying Dysautonomia - The Dysautonomia Project. (2022). Retrieved 10 October 2022, from https://thedysautonomiaproject.org/identifying-dysautonomia/

Forms of Dysautonomia. (2022). Retrieved 12 October 2022, from https://www.dysautonomiasupport.org/forms-of-dysautonomia/

Goldberger, J. J., Arora, R., Buckley, U., & Shivkumar, K. (2019). Autonomic nervous system dysfunction: JACC focus seminar. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 73(10), 1189-1206.

Mathias C J, Low DA, Iodice V et al (2012) Postural tachycardia syndrome current experience and concepts. Nature Reviews Neurology 8:22-34

Bourne, K. M., Sheldon, R. S., Hall, J., Lloyd, M., Kogut, K., Sheikh, N., ... & Raj, S. R. (2021). Compression garment reduces orthostatic tachycardia and symptoms in patients with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 77(3), 285-296.

Fu, Q., & Levine, B. D. (2018). Exercise and non-pharmacological treatment of POTS. Autonomic Neuroscience, 215, 20-27

Naschitz, J. E., Yeshurun, D., & Rosner, I. (2004). Dysautonomia in chronic fatigue syndrome: facts, hypotheses, implications. Medical Hypotheses, 62(2), 203-206.

Barizien, N., Le Guen, M., Russel, S., Touche, P., Huang, F., & Vallée, A. (2021). Clinical characterization of dysautonomia in long COVID-19 patients. Scientific reports, 11(1), 1-7.

Goldstein, D. S. (2014). Dysautonomia in Parkinson’s disease: neurocardiological abnormalities. Comprehensive Physiology, 4(2), 805.

Raj, V., Opie, M., & Arnold, A. C. (2018). Cognitive and psychological issues in postural tachycardia syndrome. Autonomic Neuroscience, 215, 46-55.

Mitro, P., Muller, E., & Lazurova, Z. (2019). Hemodynamic differences in isometric counter-pressure manoeuvres and their efficacy in vasovagal syncope. International Journal of Arrhythmia, 20(1), 1-10.

Strassheim, V., Welford, J., Ballantine, R., & Newton, J. L. (2018). Managing fatigue in postural tachycardia syndrome (PoTS): The Newcastle approach. Autonomic Neuroscience, 215, 56-61.

Shoenfeld, Y., Ryabkova, V. A., Scheibenbogen, C., Brinth, L., Martinez-Lavin, M., Ikeda, S., ... & Amital, H. (2020). Complex syndromes of chronic pain, fatigue and cognitive impairment linked to autoimmune dysautonomia and small fiber neuropathy. Clinical Immunology, 214, 108384.